The Demo That Changed Everything

Feb 21, 2026

In December 1979, a 24-year-old Steve Jobs walked into the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. He walked out with the future of computing.

This is the most expensive demo in the history of technology.

The Demo

Apple was preparing for its IPO. Xerox wanted in. Jobs agreed to let them invest, but he wanted something in return. He wanted to see what their research lab was building.

Not everyone at PARC wanted to show him. Adele Goldberg, one of the lead scientists, argued against giving a full demo. She warned management they were about to give away the store. Management overruled her.

They showed Jobs three things.

First, networking. Xerox had connected all their computers together using Ethernet. Every machine in the building could talk to every other machine.

Second, object-oriented programming. Smalltalk, a language so ahead of its time that most programmers wouldn't understand its ideas for another decade.

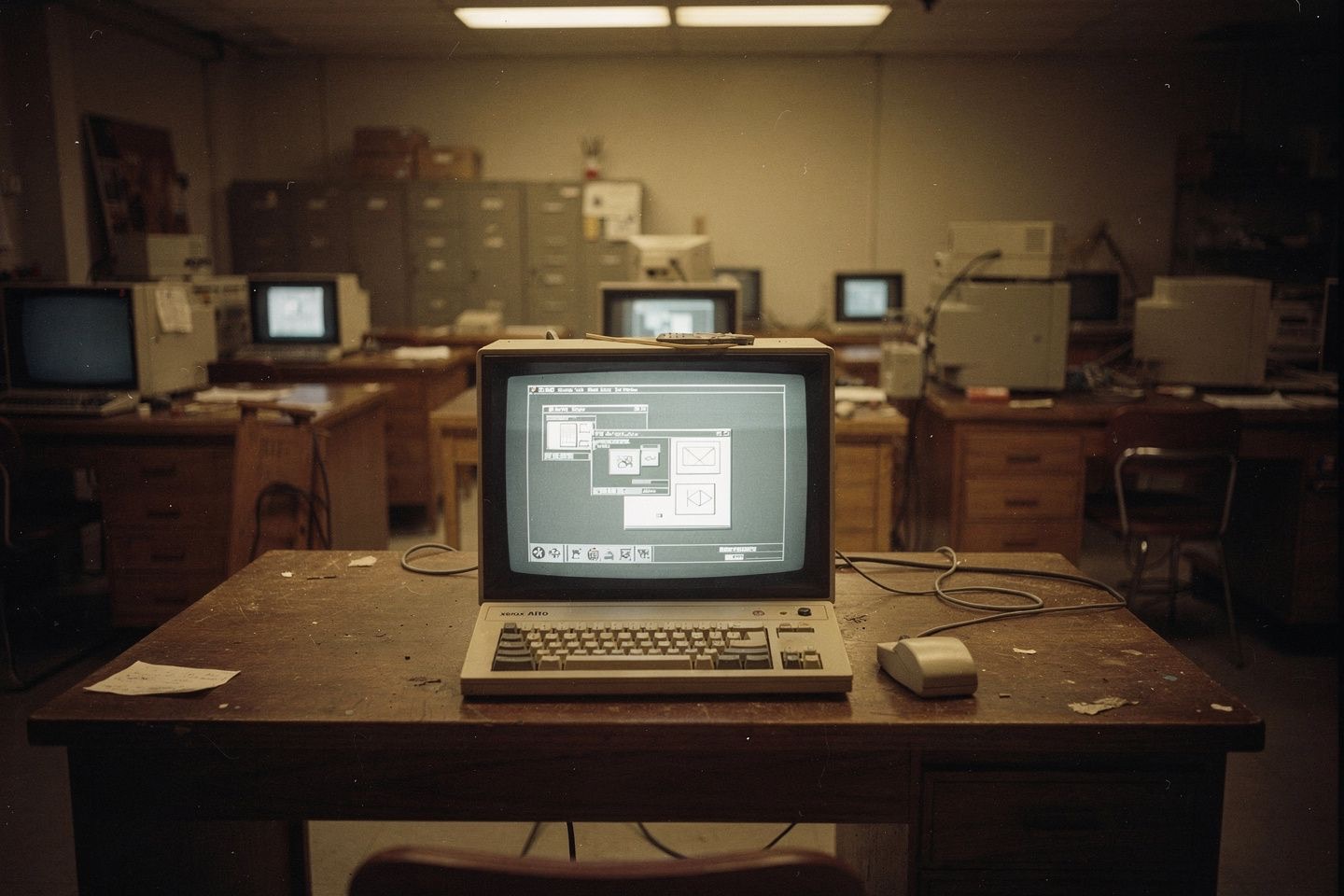

Third, the graphical user interface. A screen with windows. Icons. Menus. A cursor controlled by a small device that sat on the desk.

A mouse.

Jobs was amazed.

What Xerox had built was a prototype called the Alto. It had been sitting in their lab since 1973. Six years. The Alto had a bitmapped display, overlapping windows, a mouse, a WYSIWYG text editor, and an email client. In 1973. When most people interacted with computers through terminals connected to big, shared systems.

Xerox had a computer from the future. And they did nothing with it.

The Gap

Xerox made copiers. Their revenue came from toner and paper. The executives in Connecticut could not understand why a research lab in California was building computers. They saw the Alto and asked: but how does this sell more copiers?

It didn't. So they didn't care.

Jobs saw the same demo and asked a different question: how does this change the world?

That's the gap. Not intelligence. Not resources. Not talent. Xerox had all three. The people at PARC were some of the most brilliant computer scientists who ever lived. They knew exactly what they had built.

The gap is the question you ask when you see something new.

"How does this fit into what we already do?" versus "What does this make possible?"

One question protects the present. The other builds the future.

The Mac

Jobs went back to Apple and redirected the entire company.

January 24, 1984. The Macintosh. $2,495. A 9-inch screen, a one-button mouse, 128KB of RAM, and an interface so intuitive that the launch keynote showed the computer introducing itself. The Mac spoke its first words on stage at the Flint Center in Cupertino. "Hello. I am Macintosh."

The audience gave it a standing ovation. For a computer. In 1984.

The thing that sat in a Xerox research lab for six years, waiting for someone to care, became the foundation of modern personal computing. Every desktop, every laptop, every phone you have ever touched traces its interface back to that demo room in Palo Alto.

The GUI won. For forty years, the way humans talked to computers was visual. Windows, icons, menus, pointers. Click, drag, scroll. The entire industry organized itself around this idea. Apple, Microsoft, Google, every smartphone manufacturer on earth. All downstream of what Jobs saw that day and what Xerox failed to ship.

Forty years is a long time for any paradigm. Right now, something is changing. The most powerful tools in 2026 don't have buttons. They have prompts. More on that soon.

Pranoy Tez